The World Health Organization (WHO) declared the COVID outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern on the 30th of January 2020, and a global pandemic on the 11th of March 2020.

A pandemic is defined as “an epidemic occurring worldwide, or over a very wide area, crossing international boundaries and usually affecting a large number of people.”

So, we have the definition of how a pandemic starts, but what’s the definition for when one ends?

The simple answer is, there isn’t one.

Determining when a pandemic has ended is not as simple as it may seem.

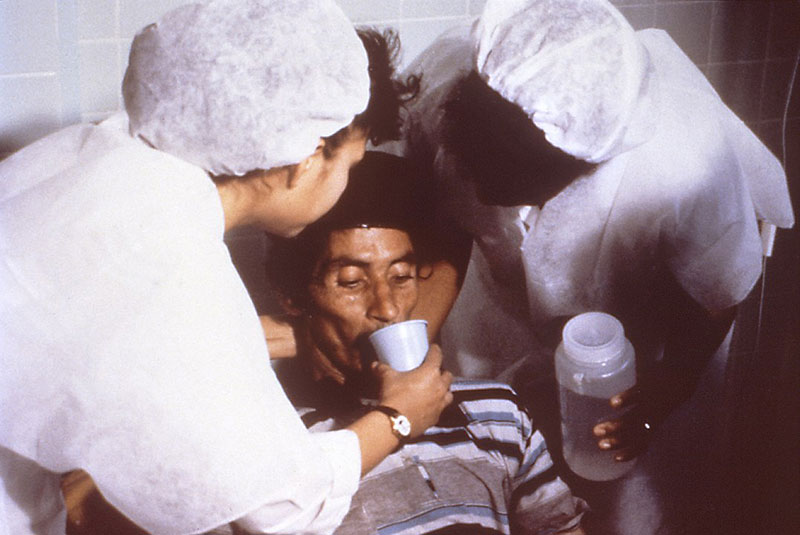

There are currently many ongoing pandemics. We have the seventh cholera pandemic which started in 1961, the strain involved still persists to this day and the WHO and other authorities believe this should still be considered as an ongoing pandemic.

An estimated 1.3 to 4 million people around the world get cholera each year and 21,000 to 143,000 people die from it.

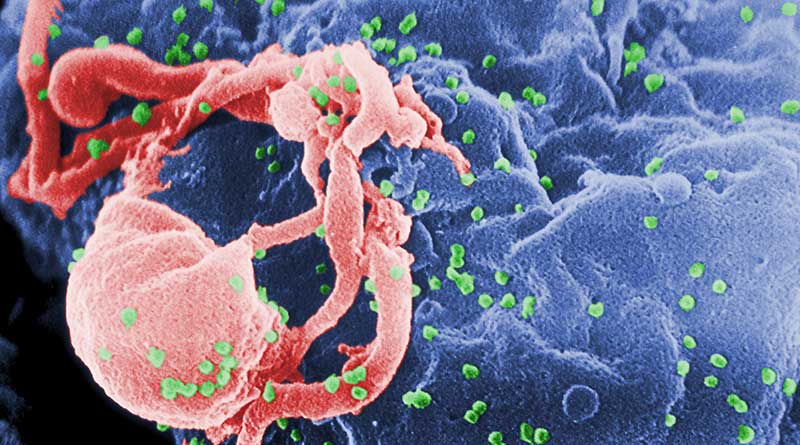

The global HIV/AIDS pandemic began in 1981 and is an ongoing worldwide public health issue. Approximately 38 million people are currently living with HIV, and tens of millions of people have died of AIDS-related causes since the beginning of the epidemic. Many people living with HIV still do not have access to prevention, treatment, and care, and there is still no cure.

While there is little doubt that the COVID-19 pandemic will eventually be declared over, there is no guarantee on how and when that will happen.

Currently, there are emergency committees of independent experts in everything from infectious diseases and community engagement to travel and trade etc, from around the world who get together every three months to review the evidence to determine if COVID is still a threat and a public health emergency of international concern.

They give their advice to the WHO, who will then determine when the acute phase of the emergency is over. This is not the same as declaring the pandemic over.

Where do we stand now?

According to Aris Katzourakis, Professor of evolution and genomics at Oxford University, we’re not coasting towards a smooth end point, we’re still in a turbulent period of the pandemic as there are still too many unknowns.

In an interview with The Inquiry, Aris stated that, there is an often-repeated idea which predicts that the virus will become less virulent over time as it evolves. The idea being that, if a virus is very harmful to its host, it will kill or immobilise them, therefore stopping the virus from being able to spread, as a result, there is selective pressure for the virus to become less harmful.

This is not the case for a virus like COVID, which does most of its spreading before it seriously harms the host, so there is no pressure for the virus to become less harmful. In the absence of that pressure there is no reason for the virus to become inherently less dangerous.

According to Aris, we don’t know which direction this virus is going to take, and whether we have severe waves in the future is yet to be determined, and any idea that it’s nearly over may be premature.

How did other pandemics end?

According to Dora Vargha Professor of history and medical humanities at the University of Exeter in the U.K., even looking back from a distance of a hundred years, historically, the end of a pandemic is very difficult to pinpoint, because they end at different times for different people all over the world.

A lot depends on personal perspective, the pandemic you are experiencing may not be the same as the pandemic someone in New Delhi in India may be experiencing.

For example, in the case of HIV/AIDS, it went from being an immediate death sentence, to a manageable chronic disease. But that only happened in societies that had the medical means and infrastructure to make it possible. In places like the U.S. and Europe, most people do not think of AIDS as an ongoing pandemic. That’s not true for many poorer parts of the world. For those people who still do not have access to prevention, treatment, and care it is still very much a public health emergency.

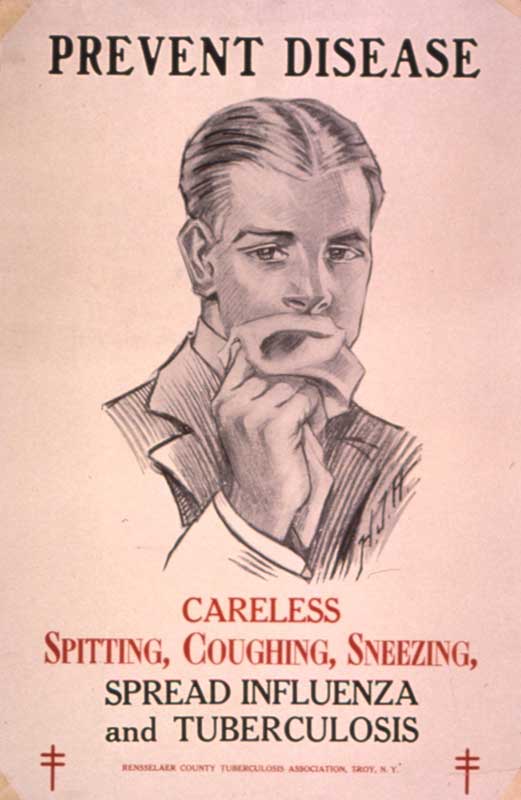

The same can be said for tuberculosis. For most of us, in our minds TB is like a disease from the 19th century, where people went to sanatoriums to recover, or in most cases, die.

In order for a pandemic to be declared over, it has to end in more ways than one.

According to Professor Nicholas Christakis a physician and sociologist at Yale University in the U.S., in order for a pandemic to really end, it has to burn out both scientifically and socially.

TB, despite being preventable and treatable, remains the world’s leading infectious disease killer, taking the lives of 1.4 million people in 2019 alone. Two billion people – one fourth of the world’s population – are infected with the TB bacteria, with more than 10 million becoming ill with active TB disease each year.

So why are we not screaming about TB from the rooftops?

The answer, says Dora Vargha, is that it has essentially become someone else’s problem. Only eight countries account for two thirds of the total global TB cases, with India leading the count, followed by countries like Pakistan, Nigeria, Bangladesh and South Africa.

The problem is smallest in the developed countries of Europe, North America, Australia and New Zealand. Where TB is a problem in these countries, it’s happening in those parts of society that wield very little social, political or economic power.

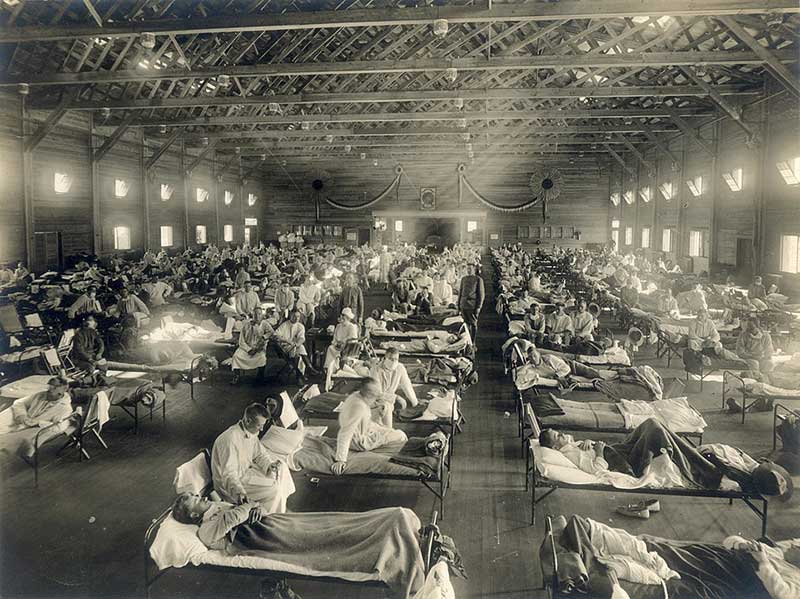

The Spanish Flu

The 1918 influenza pandemic was the most severe pandemic in recent history. It was caused by an H1N1 virus of avian origin, and it spread worldwide throughout 1918-1919. In the United States, it was first identified in military personnel in the spring of 1918.

It is estimated that about 500 million people or one-third of the world’s population became infected with the virus. The number of deaths was estimated to be at least 50 million worldwide, as it spread around the world in multiple waves mostly between the years 1918-1920.

The pandemic ended in the early 1920s, but the virus left its mark for the next 100 years.

The strand of the flu didn’t just disappear. The influenza virus continuously mutated, passing through humans, pigs and other mammals. The pandemic-level virus morphed into just another seasonal flu. Descendants of the 1918 H1N1 virus make up the influenza viruses we’re fighting today.

In Washington state in 1922, 2 years after the pandemic was considered by most people to be over, people were still getting ill. The state was still enforcing lockdown procedures and restrictions as at that time, they didn’t know if it was a new wave or something completely different.

Ann Reid, executive director of the National Centre for Science Education helped sequence the genome of the 1918 influenza virus in the 1990s. Her research found that some genetic aspects of the 1918 virus continued to be present in new outbreaks, including pandemics in 1957 and 1968.

According to Dora Vargha, diseases rarely disappear completely, they continue to be present in societies, and are either preventable, treatable or not affecting the majority of the population.

In the end, it may not be scientists or politicians who know how and when the COVID-19 pandemic is over, it will most likely be historians.

Related article: Wet bulb temperature, what it is, why it’s important and how it can kill you

If you would like to make a comment, compliment or complaint about any aspect of living or working in Hainan Island, we’d love to hear from you. We pass all communications on to the relevant services. Please keep it polite and to the point.