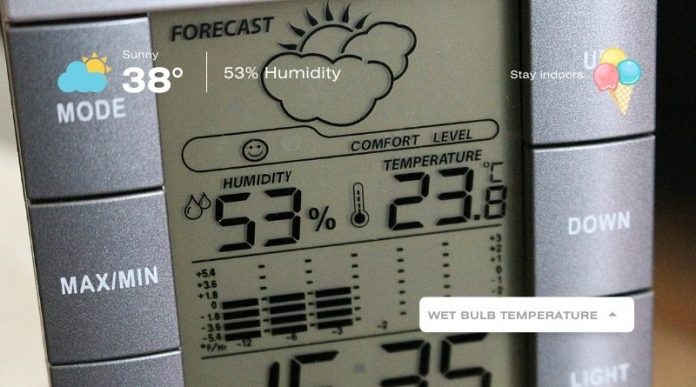

Wet-bulb temperature is the lowest temperature to which an object can cool down to when moisture evaporates from it.

Simply put, a wet-bulb temperature is a measure of heat and humidity.

Wet bulb temperatures are measured by wrapping a wet cloth on a thermometer and observing the temperature at which evaporation occurs.

When the water starts evaporating from the cloth, the temperature in the thermometer begins to decrease. How much evaporation occurs depends on the humidity.

The higher the relative humidity, the less moisture evaporates before the bulb and the surrounding air are the same temperature.

The human limit for wet-bulb temperature is 35oC, around skin temperature.

So why is wet bulb temperature important?

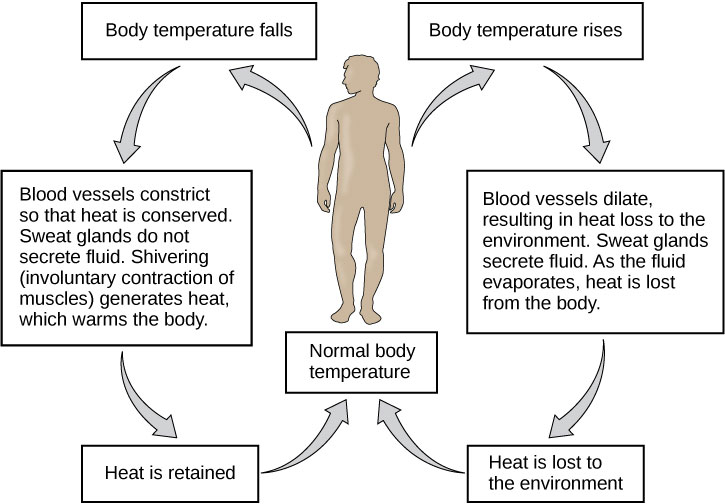

The important thing to consider here is how your body maintains its core internal temperature. It does this through;

- Sweating: Your sweat glands release sweat, which cools your skin as it evaporates.

- Vasodilatation: The blood vessels under your skin get wider. This increases blood flow to your skin where it is cooler — away from your warm inner body. This lets your body release heat through heat radiation.

Sweating is a very effective means of cooling. Humans’ ability to efficiently shed heat has enabled us to range over every continent but it’s crucial that the sweat can actually evaporate, a high wet-bulb temperature can hamper the human body’s ability to cool itself.

The human body has evolved to work at an optimum temperature range, at a high wet-bulb temperature the human body can’t lose heat, and so it gets hotter and hotter. If it gets too hot inside, you will die.

Even healthy humans cannot survive a wet-bulb temperature of 35°C for more than a few hours and being outside with a wet-bulb temperature of 32oC is dangerous.

As the wet-bulb temperature approaches your core temperature, this triggers changes in your body. You dehydrate. Your organs become stressed, especially your heart. Blood rushes to your skin to try to release heat, starving your internal organs and the results can be deadly.

So, why is this becoming an issue?

This is an issue because of what’s known as the “Clausius–Clapeyron relationship of thermodynamics”, which says that for every 1-degree increase in temperature, you see a 7 percent increase in humidity.

According to Friederike Otto, a climate scientist at Imperial College London, “this concern is becoming more urgent as climate change makes extreme heat events both more frequent and more severe.”

Since the industrial revolution (the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) refers to 1850–1900), the earth has warmed between 1.10C to 1.3 0C.

Days that approach 40oC are now being reported more regularly and wet-bulb temperatures are on the rise.

Humans cool themselves by sweating, but under these conditions when relative humidity is near 100% sweat doesn’t evaporate well so people can’t cool down even if they have shade and sufficient water.

Wet-bulb temperature is not something that humans can adapt to; the only option is to move to an area with lower temperature.

Scientists said it will be the end of the century before this affects us, right?

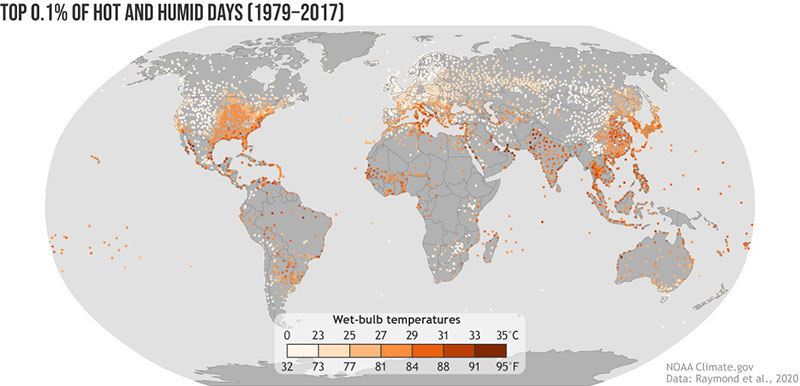

Unfortunately, not! Since 2005, wet-bulb temperature values above 95 degrees Fahrenheit (350C) have occurred for short periods of time on nine separate occasions in a few subtropical places like Pakistan and the Persian Gulf.

They also appear to be becoming more frequent. In addition, incidences of slightly lower wet-bulb temperature values in the 90 to 95-degree Fahrenheit (320C to 350C) range have more than tripled over a 40 year study.

In a recent article, The Economist calculated wet-bulb temperatures for six big cities in India using daily temperature and relative humidity readings at airports.

Four of them have exceeded 32°C in the past five years.

On May 1st, 2022, the reading in Chennai soared to 32.6°C, the highest in ten years. The temperature that day touched 38°C and was accompanied by a stifling 68% relative humidity.

Delhi was even hotter at 40°C but recorded a lower wet-bulb temperature of 24°C thanks to humidity of 23%.

This map shows locations that experienced extreme heat and humidity levels briefly (hottest 0.1% of daily maximum wet bulb temperatures) from 1979-2017. Darker colours show more severe combinations of heat and humidity.

Some areas have already experienced conditions at or near humans’ survivability limit of 35°C (95°F). Credit: Map by NOAA Climate.gov, based on data from Radley Horton.

Wet bulb temperatures will only affect tropical or third world countries, right?

Again, no.

In 2003, the UK, France, Italy, Spain and Portugal all experienced exceptional heat in the first half of August, with Portugal suffering a record 47.3°C at Amareleja in the south.

A European Union study of 16 nations puts the number of excess deaths across the bloc during that heatwave as between 50-70,000, at wet-bulb temperatures close to 79°F, (26.1°C) with France and Italy each seeing between 15,000 and 20,000 fatalities.

The summer of 2019 brought two heatwaves, in late June and mid-July, which left about 2,500 people dead.

Last year (2021) was Europe’s hottest summer on record, according to the European climate change monitoring service Copernicus.

Between late July and early August 2021 temperatures in Greece hit 45°C,

In France, temperatures hit a record 46°C on June 28th in the southern town of Verargues. Thousands of schools were closed.

In Spain, temperatures reached 47°C in parts of the south.

If we just turn on our air conditioners this will help solve the problem, right?

Just 12 percent of India’s population of 1.4 billion citizens have access to air conditioning, which means hundreds of millions of people are simply unable to cool themselves when their bodies reach the point of heatstroke.

And this is a situation that’s mirrored across many poorer countries.

But it’s not just a problem for poorer countries. “The knock-on effects of heat are extraordinary,” said Rachel Kyte, dean of the Fletcher School at Tufts University, who co-authored a 2018 report titled “Chilling Prospects: Providing Sustainable Cooling for All.” (The 2022 version of the report is available here.)

That adds up to a huge economic toll. By one estimate, heat costs the US economy $100 billion per year, a number poised to rise to $200 billion by 2030 and $500 billion by 2050 if nothing is done to mitigate climate change.

This is something that just affects people, right?

Again, no..

Just like humans, sweating (along with panting) is a major way for some farm animals like cattle to try to control their body temperature and avoid overheating.

June 16th 2022, CBS News in the US reported over 2000 cattle deaths in Kansas.

Thousands of cattle in feedlots in southwestern Kansas died of heat stress due to soaring temperatures, high humidity and little wind.

According to A.J. Tarpoff, a cattle veterinarian with Kansas State University, “temperatures rose, but the more important reason why it was so injurious was that we had a huge spike in humidity … and at the same time wind speeds actually dropped substantially.”

Most of us have grown up listening to (even the most ardent) climate change scientists discuss climate models that projected combinations of heat and humidity that could reach deadly thresholds for anyone spending several hours outdoors by the end of the 21st century.

The study, “The emergence of heat and humidity too severe for human tolerance,” published in 2020 in Science Advances shows that for the first time some locations have already reported combined heat and humidity extremes above humans’ survivability limit.

Dangerous extremes only a few degrees below this limit have occurred thousands of times globally.

It’s now being internationally recognised that there is a serious challenge posed by humid heat that is more intense than previously reported and increasingly severe.

These extremes are already happening — decades before anticipated — due to global warming that has already happened to date.

Related article: Hot tips for keeping your doggies cool this summer