China’s Push to Detect Lunar Ice Using Earth-Based Radar Tech

May 2025, in a major step for lunar exploration, Chinese scientists have carried out the first large-scale effort to detect water ice near the Moon’s south pole using two powerful radar systems on Earth.

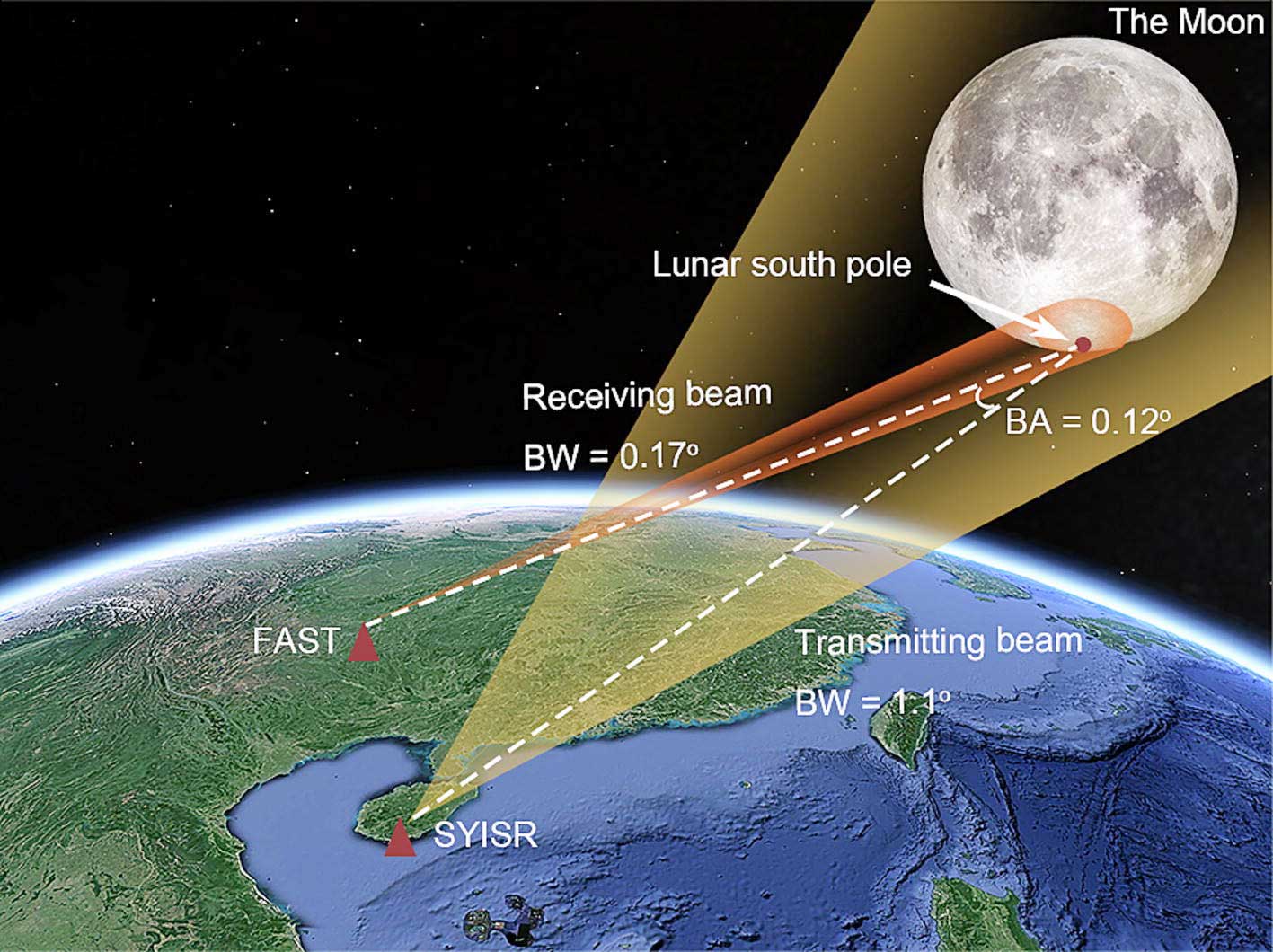

The experiment, which paired the Sanya Incoherent Scatter Radar (SYISR) in Hainan with the Five-hundred-meter Aperture Spherical radio Telescope (FAST) in Guizhou, marks the most advanced ground-based radar scan of the Moon to date. It also highlights China’s rising commitment to both the science and strategy behind lunar exploration.

A New Way to Hunt for Ice on the Moon

The research, published in Science Bulletin, suggests that up to 6% of the surface material, known as regolith, in some of the Moon’s permanently shadowed regions (PSRs) may contain buried ice. This ice may be found in scattered pockets, several meters below the surface. While the data doesn’t offer a conclusive answer, it does give future missions a solid starting point for where to look and how to plan for using local resources.

To carry out the experiment, the team used a method called bistatic radar, where one location sends a radar signal and another listens for the echo. In this case:

SYISR, a powerful radar normally used to study Earth’s upper atmosphere, sent out wide radar beams aimed at the Moon’s near side.

FAST, the world’s largest radio telescope, acted as a receiver, tuned in to listen for radar echoes from the Moon’s near side, focusing on the south polar region.

The Five-hundred-meter Aperture Spherical radio Telescope (FAST) is located in a naturally deep and round karst depression in Guizhou Province, in southwest China. This remote site was specifically chosen for its natural topography, which provides shielding from radio frequency interference, making it ideal for sensitive astronomical observations

By combining these tools, the team captured radar data at a resolution of about 500 meters by 1.2 kilometers across key parts of the Moon’s south pole, (each individual pixel or data point in their radar images represents an area on the lunar surface that is approximately 500 meters wide and 1.2 kilometres long.)

What the Signals Suggest

The researchers focused on a radar property called the circular polarization ratio (CPR). High CPR readings can hint at buried ice, since ice scatters radar signals in a particular way.

But CPR can also be influenced by rough surfaces or rock debris, so it’s not a smoking gun.

To get a clearer picture, the team compared their radar data with:

- Neutron measurements that detect hydrogen (a sign of water),

- Temperature models showing which areas stay cold enough to preserve ice,

- And previous mission data, like NASA’s and India’s radar instruments.

What They Found

Ice Content: Some shadowed regions might hold up to 6% ice by weight in the top 10 meters of soil. That’s an upper limit, not a typical average.

Depth: Most of the possible ice deposits appear to be 5 to 7 meters underground. Some may be closer to the surface, but likely in smaller amounts.

Spread: The ice is probably broken up and patchy—not in thick sheets as some earlier theories suggested.

Why It Matters

Mining Challenges

Getting to this ice won’t be easy. Because it’s buried and scattered, missions will need specialized tools to drill, melt, or extract it, driving up both costs and technical demands.

Choosing Where to Land

This data will help mission planners zero in on landing spots where the ice is more accessible. That’s crucial for upcoming efforts like China’s Chang’e-7 mission and the International Lunar Research Station (ILRS) project, both aiming to explore the south pole in the next decade.

Bigger Picture: Science and Strategy

This project is a breakthrough in using Earth-based radar to study the Moon. It also helps double-check the accuracy of space-based instruments like NASA’s ShadowCam, offering a new layer of “ground truth” from Earth.

Strategically, it puts China at the front of a growing race to explore lunar water ice.

Other key players include:

NASA’s Artemis program, which aims to land astronauts at the Moon’s south pole,

India’s Chandrayaan-4, in early planning, may include underground drilling to confirm ice presence.

Russia’s Luna-27, which plans to carry instruments for detecting water-related elements, though its timeline remains uncertain.

China’s radar setup even surpasses older U.S. systems like the now-decommissioned Arecibo–Green Bank pairing, offering finer detail and better sensitivity.

Limits and Unanswered Questions

Despite the success, the researchers stress a few key limitations:

Uncertainty in CPR Readings: Lead scientist Li Mingyuan noted that CPR alone can’t confirm the presence of ice. Future missions will need direct sampling or more advanced radar to be sure.

Limited Coverage: This radar scan mostly covered crater slopes, not the deepest and coldest parts of the south pole, precisely where ice is most likely to survive.

Economic Hurdles: Some experts doubt that 6% ice is worth extracting with today’s technology. Others argue that even small amounts, if harvested efficiently, could support fuel production and life support systems.

What’s Next?

Chang’e-7 (2026) will send a mini flying probe equipped with a water sensor to confirm these findings from up close.

ILRS Phase 1 (2030) the first phase of the International Lunar Research Station, led by China and Russia, plans to test technologies that could extract ice using microwave heating.

As more missions zero in on the Moon’s south pole, studies like this will be crucial. They won’t just shape where we go next, they’ll help decide how we survive, build, and work on the Moon in the years to come.

Related article: China Sets World’s Toughest EV Battery Safety Standard “No Fire, No Explosion” Rule Comes into Force 2026