April 10th, 2022 President Xi Jinping inspected a seed laboratory in Sanya and stressed the crucial role of “Chinese seeds” in ensuring the country’s food security.

So why is there such a focus on achieving self-reliance in seed technology?

Most people, as they do their daily grocery shopping don’t stop to think about diversity in agricultural systems, it’s simply not on their radar, it doesn’t make front page headlines or attract a lot of attention.

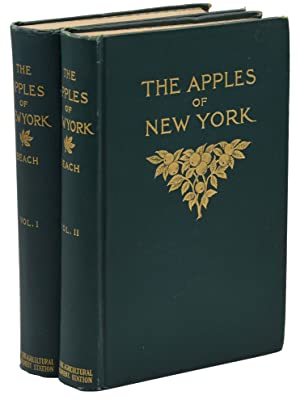

But have you ever wondered why all the bananas look uniform in size and shape, or why there are so few varieties of apples on display in the supermarket?

It’s worth taking a minute to consider it.

In the United States in the 1800’s (that’s where we have the best data from), farmers were growing 7,100 different named varieties of apples.

Today, 6,800 of those are extinct.

Crop diversity is the biological foundation of agriculture, and that foundation may not be as solid as you might imagine.

According to some scientists, a mass extinction is under way in the fields and the agricultural system, and this mass extinction is taking place without people really noticing.

“The rapid loss of the world’s biological diversity, is increasingly recognised as one of the most pressing issues of our time. Sitting alongside and interlinked with climate change, this crisis needs addressing.”

DAN SALADINO, AUTHOR OF LAST HARVEST: THE FIGHT TO SAVE THE WORLD’S MOST ENDANGERED FOODS

There are about 35-40,00 different varieties of beans in the world, 200,000 different varieties of wheat, and 200-400,000 different varieties of rice.

But it’s being lost.

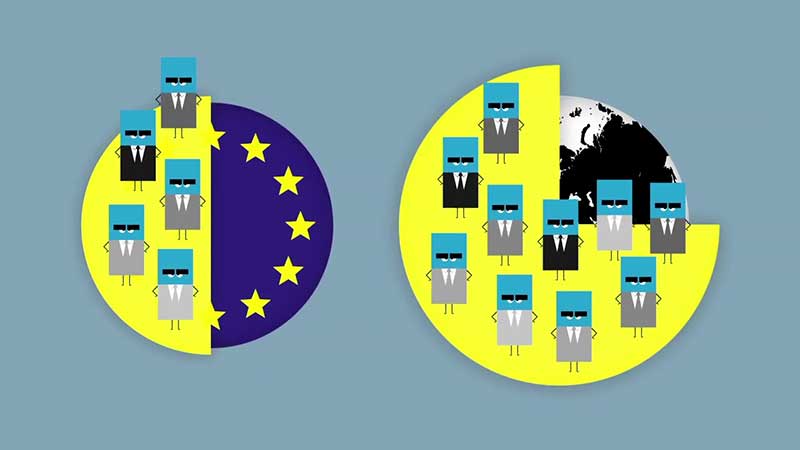

So why is this happening? Let’s take a look at Europe as one example.

Since the beginning of agriculture, farmers have selected those plants that were best adapted to their environment and saved the seeds in order to resow them the following season. Through this process, farmers have been able to develop a wide variety of crops that are adapted to their environments.

But that was before bureaucracy and red tape.

In 1970, the European directive created the common catalogue of varieties of agricultural plant species.

To be marketed in Europe, a seed has to be registered in this catalogue. But this is not an easy process.

First, there is an extremely complicated application procedure.

Second, there are the registration fees which can cost up to thousands of euros.

And finally, seeds are assessed against 3 criteria,

- Distinctiveness

- Uniformity and,

- Stability

These criteria, like the rest of the procedure, favour standardised seeds meant for industrial agriculture, not farm saved seeds which are by nature unstable. It is this instability which makes them better at adapting to their environment.

The catalogue contains 34,500 varieties which may seem like a lot, but pales in comparison to the real genetic diversity in nature, and it is this diversity that is the best defence against natural disasters.

But these kinds of seeds are at risk, as they are being replaced by industrial scale, monocultures of standardised uniform plants. Loss of biodiversity means loss of food security.

Europe is the biggest seed exporter, supplying 60% of the world market, 75% of which is controlled by just 10 huge seed companies and also agrichemical companies. Trapped into buying corporate seeds tailor made for use with agrichemicals, farmers lose their independence, and become dependent on costly inputs. Preventing farmers from sowing and exchanging seeds stops centuries old innovation.

Bio diversity is essential to help the world feed itself.

The looming question for the 21st century is “what’s going to happen to agriculture in an era of climate change, what kind of traits and characteristics do we need in our crops to be able to adapt?”

If crops cannot adapt to climate change in the 21st century, neither will agriculture and neither will we.

In the future, in many countries, the coldest growing seasons are going to be hotter than anything those crops have seen in the past. Is agriculture going to be able to adapt to this?

The good news is that we have started collecting and conserving a great deal of biological diversity, mostly in the form of seeds. We have stored them in buildings all around the world which we call seed banks, essentially great big freezers.

To conserve seeds long term and make them available to plant breeders and researchers, you dry them and then you freeze them.

Unfortunately however, even these seed banks can be vulnerable, and disasters have happened. In recent years the seed banks in Iraq, Afghanistan, Rwandan and the Solomon Islands have been lost. Then there are smaller daily disasters that occur through these banks having financial issues, machine failure and human error, all of which results in loss of diversity.

Think of losing diversity in this scenario not in the same way as losing your car keys, but rather in the same way as losing the dinosaurs, once it’s gone, it’ll never be seen again.

September 23rd, 2019 the UN’s Secretary-General António Guterres said, “the preceding four years had been the four hottest on record, and we are starting to see the life-threatening impact of climate change on health… and risks to food security.”

Regenerating the world’s biodiversity and fostering higher levels of diversity in our food system is essential for security and resilience – and ultimately for our survival.

Related article: Newborn rare gibbon spotted in Hainan national park