Li Minority people’s culture on Hainan Island, an in-depth guide, part 3 textiles

Hainan Island is considered as one of the birth places of China’s textile industry. Spinning wheels and needles have been discovered dating as far back as the Neolithic period. In the Spring and Autumn periods (771-453 BCE), fabric (woven shells), was already leaving Hainan as tribute to the imperial court, Zhou Dynasty. By the Han Dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE) “broad cloth” was favoured by the court.

Li Minority environment Hainan Island

As the Li people were mostly concentrated in mountainous regions with deep valleys and rivers they were surrounded by tropical rainforests and rich plant resources. In total there are more than 100 species of plant belonging to the category “fibres” such as wild hemp or cotton growing locally. These pliable fibre materials provided the necessary material conditions for the textile industry to blossom in Hainan.

The spread of Li Minority textiles

At the end of the Song Dynasty (960 – 1279 CE) Huang Daopo, an envoy between the Li and Han cultures, travelled along the Songjiang river spreading Hainan’s advanced textile techniques to the areas south of the Yangtze River, as a result of which, Hainan’s textiles gradually became adopted by the whole country. Studies spanning the thousands of years of Hainan’s textile culture can trace the influence of Hainan’s textiles on China’s textile industry as a whole, illustrating its historical significance.

Evolution of Li Minority textiles in Hainan

Hainan’s textile industry evolved from non-woven fabrics to weaving and then linen and cotton textiles. The Island became famous for its cotton products. Records show that as far back as 3,000 years ago the Li people were already planting cotton, and spinning and weaving.

Since the Han Dynasty their weaving products such as “wide cloth”, “Coloured cloth” and “Li curtain” were sent as tributes to the royal courts of all dynasties. Before the Yuan Dynasty (1279 – 1368 CE) its cotton textile technology was far more advanced than the central plains.

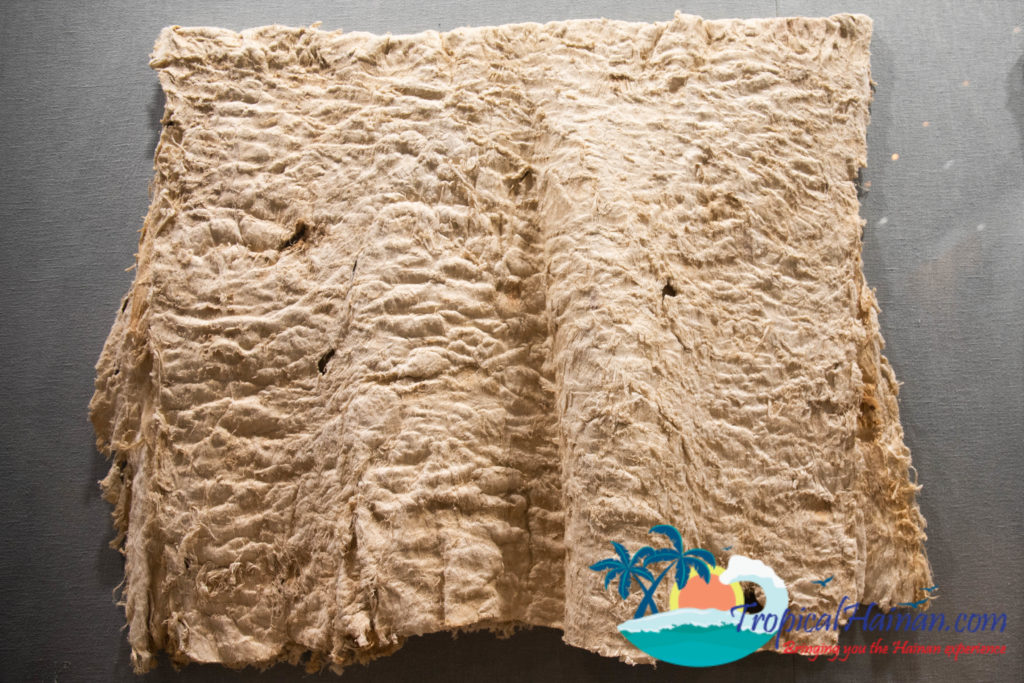

Li Minority Bark cloth (Na cloth)

Bark cloth, also known as Na cloth, paper cloth and grain skin cloth first appeared in the Neolithic era. It was used in the non-weaving period prior to the use of hemp and cotton. It was also the raw material used for clothing in other parts of the south of China in ancient times.

Bark cloth is an ancient technique of processing bark from a tree into a non-woven fabric, and the practice is still preserved today in some Li villages. There are a complex set of processes involved that can be broken down (simply) as removing the bark, trimming, soaking, patting, and sewing.

The development of ancient textile technology began from the collection of wild plant fibres. In the Neolithic period plants used would have consisted mainly of kudzu and hemp, which were spun by hand or spinning wheel and made into daily necessities.

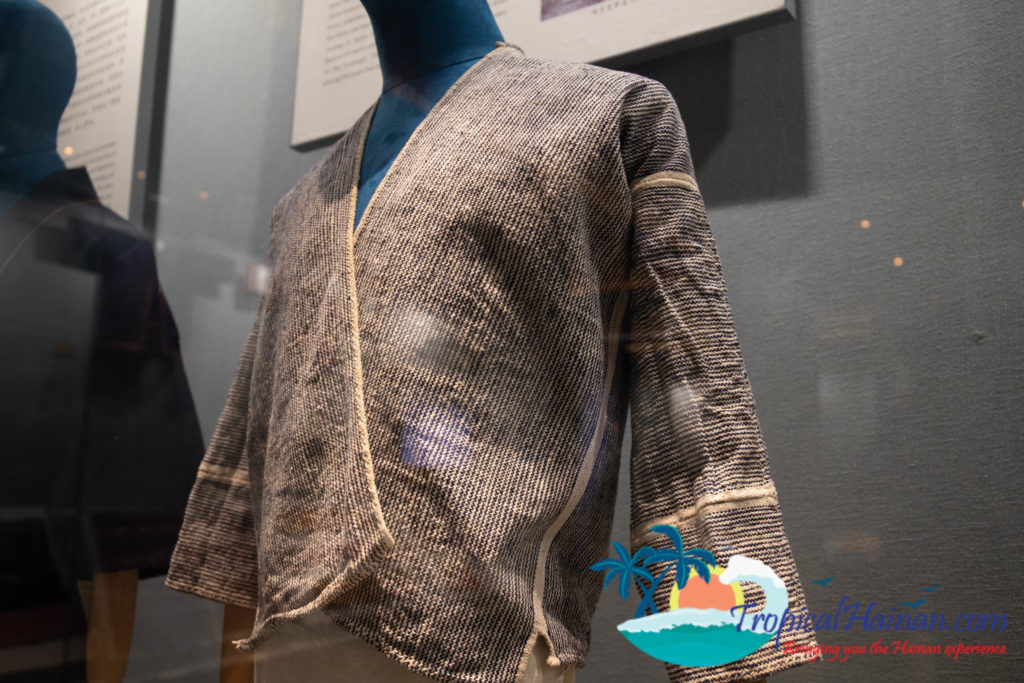

Broad cloth was first seen in the Qin (221-206 BCE) and Han Dynasties (206–220 BCE) when it became a tribute to the imperial court. The earliest Broad cloth is a piece of cloth with a hole cut in the middle which people would put their head through. This ancient system of garments can still be seen from the “Head through Dress” of the Run-branch of Li women.

The head through dress has a v-shaped neckline with ornaments of double sided embroidery at the collar, cuffs and hem.

Li Minority textiles raw materials

Hemp textile raw materials mainly include helicteres isora, mimosacaea entada, rattan as well as sheep hoof cane, additionally they also used tapa bark and arrowhead bark. Hemp processing technology includes cutting, soaking, thrashing, rubbing, boiling, and drying to allow the hemp fibre to be separated into hemp threads ready for spinning.

Helicteres Isora, called “bian” in the Li language is a shrub about 2 metres tall with oval leaves and reddish or purple flowers. It grows in Hainan’s forests and the fibres can be made into paper or raw materials for weaving.

Bauhinia Kerrii, also called Qiongdao sheep hoof cane and known as “Ma” in the Li language is a vine tree and a common plant in Hainan. It grows at a middle to high elevation and its stem is used to make straw sandals and fibre for cloth.

Entada phaseoloides is known locally as “glasses bean”, “ox eyes”, “river crossing dragon”, or “ox intestine hemp”. In the Li language it is called “Miaochongren” and is an evergreen wooden vine also found in Taiwan, Guangdong, Guangxi and Yunnan. It grows close to mountain streams in the forest and can be found climbing large trees.

Hainan Island has been rich in cotton since ancient times, it is the main raw materials for Li women’s textiles. Song Dynasty literature mentions “Jibei, it is rich in Lei Hua, Lianzhou, and Lidong of South China and can be used instead of silk.” “Hainan people use it to weave many things”. Here, “bei” and “Jibei” refer to cotton in the Li language. Jibei refers to kapok cotton.

Li minority pedal spinning wheel

Ancient techniques for spinning evolved through three distinct stages, twisting by hand, spinning with a rod and spindle and the spinning wheel.

Hand twisting is the oldest human spinning technique.

Traditional Li Minority textile dyes

| Name | Also known as | Main parts in use | Colour | Method |

| Sappan | Logwood | Heartwood | Orange and reddish brown | Boil to a liquid, add grass ash for dying |

| Wood blue Hair indigo False indigo | Sophora blue Hirsute indigo Small indigo | Stem and leaves Leaves Stem and leaves | Blue and dark blue | Fermentation for making indigo mud for dying |

| Memecylon Ligustrifolium Champ ex Benth | Angle wood | Leaves | Green | Juicing to a dye |

| Tumeric | Tumeric | Root | Yellow | juicing to a dye |

| Wenchang cone Syzgium cumini Rubia | Castanopsis echidnocarpa Duhat Humulus scandens | Bark Bark Root | Red purple brown Brown and black Red | Juicing into a dye, adding snail ash Juicing into a dye mud for dying Juicing into a dye |

Li Minority looms

The squat waist loom used by the Li people is one of the oldest known loom structures on the island. Traditionally it was comprised of a rattan (or bark) belt, a waist force stick, a weft beating knife, a warp pulling stick, a heddle shaft, a bamboo weft needle and a shuttle.

The waist loom is used for what’s called single sided weaving, i.e. the cloth has a pattern on one side and is plain on the other. This technique is used mainly for quilts, garments and headscarves.

The foot loom, unlike the more primitive waste loom is a complete loom equipped with shuttles, warp shaft, rolling shaft, heald (single heald) pedals and a frame.

Li Minority embroidery on Hainan Island

Originally Li Minority embroidery resulted from the need to make their garments more durable, only later did it evolve into decoration for aesthetics. Its main function was to line and protect the edging of garments.

Li embroidery can be both single and double sided. In single sided embroidery they use a technique called “pulling”, which is used to emphasise the woven pattern of the garment. They embroider contrasting coloured lines through the weave to enhance the pattern effect.

Double sided embroidery requires that both sides of the garment should be uniform. In Hainan the Run-branch women from Baisha are perhaps most famous for this embroidery technique.

The artistic style of Li Minority stems from a primitive art form with characteristics of ancestor worship and animism. They favour blue, black and red. Most brocade use black and blue lines in the bottom warp. Traditionally men would wear red cloth on their head and a red belt. Women’s tube skirt would have a main pattern in red with the lace and button sections also decorated with red thread.

The Li Minority peoples are divided into five dialect branches with varying embroidery types and styles with varied patterns showing diversified cultural features and aesthetic tastes.

Li Minority Dragon Quilt

The traditional Dragon Quilt of the Li people uses hemp and cotton (sometimes silk) as raw materials. The patterns and colours are fairly simple and comprised of three, four, five or seven separate parts. Largely they use brown, coffee, yellow, black and blue as base colours and are decorated with lines representing humans or animals or geometric patterns in white, black, blue, brown or yellow.

They are generally 1.4 – 2.4 metres long and 1.2 – 1.6 metres wide. The quilts are woven in waist looms and are known as the “large quilt”, “adopted quilt” or “funeral quilt” in the Li language. They can be used as sacrificial objects and are also exquisite works of folk art from the Li People. They most often depict religious beliefs and folklore activities, such as funerals, ancestor worship or even raising the beam of a new house.

They play an important role in depicting the social lives of the Li people with dual connotations of religion and social politics and are considered a very important cultural heritage.

Traditional Li Minority Men’s costumes

Traditionally, Li men’s garments reflected the tropical climate and culture and were divided into 4 main types. First an under garment that is open at the front, collarless and button less, made from hemp or cotton with shorts. Next they’d wear hemp or cotton coats, again collarless and open at the front with short skirts forked at the sides. Over this they’d wear short sleeved, collarless black coats, open at the front and black short skirts forked at the front and rear.

The most prominent feature of men’s attire would be a red or black turban with a hair knot on the forehead the style and position of which would vary amongst branches.

Traditional Li Minority women’s costumes

Depending on the branch, Li women’s costumes would have their own unique features and styles. There are two major types of women’s coats, pullovers and coats which are collarless and open at the front, both of which would be embroidered with exquisite patterns on the sides, lower hems, back, cuffs, collars and front left and right.

Their skirts are separated into short, medium or long.

Skirts and coats would generally contain flower patterns as well as depicting humans, animals, grasses and geometric designs. Typically, married Li women would tie their hair up at the back and wear patterned head scarves, decorated with bone, silver or copper.

Except for women of the Sai branch, women from all other four branches would have extensive tattoos on their bodies.

Since the beginning of this century, traditional textile culture in Hainan has received a lot of attention worldwide. In 2003 it was listed by the Ministry of Culture as one of the top 10 national folk culture protection projects in the country.

In 2006 it was named by the state council in the first batch of state level intangible cultural heritage protection directory.

In October 2009, it was approved by the UNESCO Fourth Governmental Committee meeting to be listed as intangible cultural heritage in urgent need of protection.

Relate article: Li Minority culture on Hainan Island, an in-depth guide, part 4 jewellery